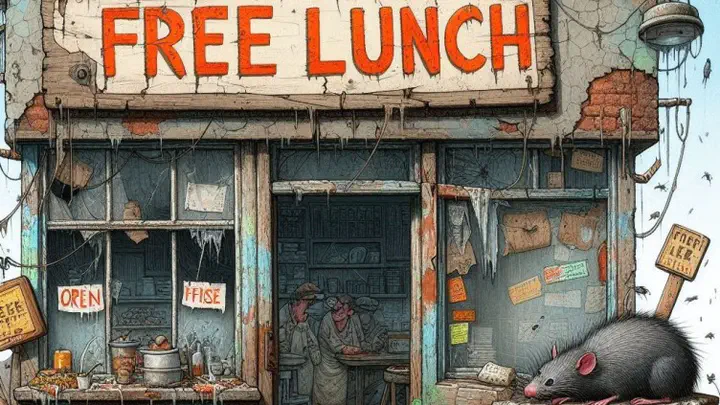

Prediction markets are not a free lunch

Many prediction markets implicitly depend on less-informed traders, gamblers, or hedgers to subsidize information discovery. This is an unreliable way to fund the production of collective forecasts. Prediction markets should be explicitly funded by sponsors who want the information that the markets elicit and aggregate.

“There’s no such thing as a free lunch,” is a popular saying among economists: In life, we shouldn’t expect to get something for nothing. This includes information; gathering data and analyzing it requires effort and resources. Prediction markets, which allow people to bet on the outcome of future events, purport to provide cash incentives to forecast these events but, if this is true, where are the incentives coming from?

You would be wary of accepting a wager from anyone who wants to bet with you about something you don’t know much about.

Most pay-to-play prediction markets are “zero sum”, in which the winnings of those who are correct must come from the losses of those who are wrong. Often the organizers of the prediction market take a fee, so the total amount won by all participants is necessarily less than the total amount they bet in the market. People who have relevant information about future events have a motive to take part in a market like this, but who will they bet against? You would be wary of accepting a wager from anyone who wants to bet with you about something you don’t know much about, because you would assume they knew something that you did not. Economists Paul Milgrom and Nancy Stokey formalized this idea in what became known as the “no-trade theorem”.

Sports betting is a multi-billion dollar industry in which gamblers collectively lose money to bookmakers and sports betting platforms. Other topics, such as national elections and the Oscars, can also have enough activity for zero-sum markets to work. But, the success of prediction markets for sports and entertainment obscures the fact that the ability of these topics to attract uninformed participants to effectively subsidize information discovery is unusual. For anyone who wants the information that these prediction markets provide they are the proverbial free lunch. Many people who bet on sports have motives that are not purely financial. Betting on a sports match might heighten the excitement of watching it. Winning can cause a release of dopamine which can lead to addictive behaviour. The existence of problem gambling suggests that some gamblers are not the rational agents found in the models of economists.

Prediction markets for more specialized topics, such as climate, have struggled to attract the kind of interest that sports betting does. This might be because participants, and potential participants, are displaying a higher level of rationality than is found in sports gamblers: less-informed people don’t want to bet against better-informed ones, so the better-informed ones have no incentive to take part. Perhaps prediction markets for more esoteric subjects could adopt some of the behavioural tricks used by bookmakers to entice people to bet. However, apart from the ethical concerns this would raise, it is also questionable whether encouraging people to behave less rationally is desirable when the goal of a prediction market is to elicit and aggregate information as accurately as possible.

…a skilful forecast may allow people to reduce or eliminate their exposure to risk…

If gamblers won’t pay for our lunch another potential source are hedgers: People who will bet on an outcome not because they think that it will happen but because they want to be compensated if it does happen. In some situations, however, the existence of a skilful forecast may allow people to reduce or eliminate their exposure to risk, so there is no need for them to hedge it. For example, a good forecast of likely sea-level rise might enable the construction of appropriate sea defences, reducing the need to insure against flooding. Indeed, forecasts that are too accurate can cause insurance markets to break down by allowing for adverse selection in which only people highly likely to claim want to buy cover.

Gamblers and hedgers are an unreliable way to fund the provision of information. Rather than hope that these groups will indirectly pay for information it makes more sense for prediction markets to be funded directly by sponsors who want information. In a sponsored market a market maker takes the role of the uninformed participants. Unlike traditional market makers in financial markets, who are motivated by profit, the market maker’s goal is to lose money in return for good information. Market making algorithms can be based on “proper scores” commonly used to evaluate probability forecasts. These incentivize participants to bet based on their true beliefs about the probabilities of different outcomes.

Prediction markets are vulnerable to “free riders” who can obtain the benefits of the information without paying for it.

An obstacle to finding sponsors for prediction markets is that if the prices in the prediction market are publicly available the information being generated by the market — which is embodied in the prices — is available to anyone. The market is vulnerable to “free riders” who can obtain the benefits of the information without paying for it. This is a typical problem faced by “public goods” which are non-rival (one person having the information doesn’t preclude someone else from having it) and non-excludable (it’s difficult to restrict access to the information). Such goods can be provided by the government, who can effectively force everyone to contribute through taxation. They can also be provided privately using “assurance contracts”, in which beneficiaries agree to contribute on the condition that a critical mass of other beneficiaries also agree to contribute.

Prediction markets should be sponsored by organisations who want forecasts that reflect the collective judgement of market participants. The principal purpose of a prediction market is to make predictions, not to allow the hedging of risks or to provide entertainment. Confusing these aims is likely to result in markets that do not achieve any of them satisfactorily.

The original version of this post appeared 9 June 2025 on LinkedIn.